Archaeology and the New Testament

| by | Kyle Butt, M.Div. |

Any time a book alleges to report historical events accurately, that book potentially opens itself up to an immense amount of criticism. If such a book claims to be free from all errors in its historical documentation, the criticism frequently becomes even more intense. But such should be the case, for it is the responsibility of present and future generations to know and understand the past, and to insist that history, including certain monumental moments, is recorded and related as accurately as possible.

The New Testament does not necessarily claim to be a systematic representation of first-century history. It is not, per se, merely a history book. It does claim, however, that the historical facts related in the text are accurate, with no margin of error (2 Timothy 3:16-17; Acts 1:1-3). It is safe to say that, due to this extraordinary claim, the New Testament has been scrutinized more intensely than any other text in existence (with the possible exception of its companion volume, the Old Testament). What has been the end result of such scrutiny?

The overwhelming result of this close examination is an enormous cache of amazing archaeological evidence that testifies to the exactitude of the various historical references in the New Testament. As can be said of virtually every article on archaeology and the Bible, the following few pages that document this archaeological evidence only scratch the surface of the available evidence. Nevertheless, an examination of this particular subject makes for a fascinating study in biblical accuracy.

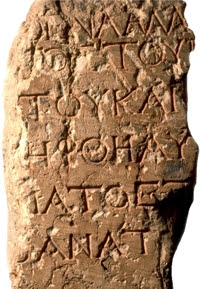

THE PILATE INSCRIPTION

Few who have read the New Testament accounts of the trial of Jesus can forget the name Pontius Pilate. All four gospel accounts make reference to Pilate. His inquisition of Jesus, at the insistence of the Jewish mob, stands as one of the most memorable scenes in the life of Jesus. No less than three times, this Roman official explained to the howling mob that he found no fault with Jesus (John 18:38; 19:4,6). Wanting to placate the Jews, however, Pilate washed his hands in a ceremonial attestation to his own innocence of the blood of Christ, and then delivered the Son of God to be scourged and crucified.

|

| Discovered in 1961, “The Pilate Inscription” offers remarkable archaeological testimony that a man named Pontius Pilate once governed Judea. Credit: Zev Radovan, Jerusalem. |

What can be gleaned from secular history concerning Pilate? For approximately two thousand years, the only references to Pilate were found in such writings as Josephus and Tacitus. The written record of his life placed him as the Roman ruler over Judea from A.D. 26-36. The records indicate that Pilate was a very rash, often violent man. The biblical record even mentioned that Pilate had killed certain Galileans while they were presenting sacrifices (Luke 13:1). Besides an occasional reference to Pilate in certain written records, however, there were no inscriptions or stone monuments that documented his life.

Such remained the case until 1961. In that year, Pilate moved from a figure who was known solely from ancient literature, to a figure who was attested to by archaeology. The Roman officials who controlled Judea during Jesus’ time, most likely made their headquarters in the ancient town of Caesarea, as evinced from two references by Josephus to Pilate’s military and political activity in that city (Finegan, 1992, p. 128). Located in Caesarea was a large Roman theater that a group of Italian-sponsored archaeologists began to excavate in 1959. Two years later, in 1961, researchers found a two-foot by three-foot slab of rock that had been used “in the construction of a landing between flights of steps in a tier of seats reserved for guests of honor” (see McRay, 1991, p. 204). The Latin inscription on the stone, however, proved that originally, it was not meant to be used as a building block in the theater. On the stone, the researchers found what was left of an inscription bearing the name of Pontius Pilate. The entire inscription is not legible, but concerning the name of Pilate, Finegan remarked: “The name Pontius Pilate is quite unmistakable, and is of much importance as the first epigraphical documentation concerning Pontius Pilate, who governed Judea A.D. 26-36 according to commonly accepted dates” (p. 139). What the complete inscription once said is not definitely known, but there is general agreement that originally the stone may have come from a temple or shrine dedicated to the Roman emperor Tiberius (Blaiklock, 1984, p. 57). A stronger piece of evidence for the New Testament’s accuracy would be difficult to find. Now known appropriately as “The Pilate Inscription,” this stone slab documents that Pilate was the Roman official governing Judea, and even uses his more complete name of Pontius Pilate, as found in Luke 3:1.

POLITARCHS IN THESSALONICA

When writing about the Christians in Thessalonica who were accused of turning “the world upside down,” Luke noted that some of the brethren had been brought before the “rulers of the city” (Acts 17:5-6). The phrase “rulers of the city” (NKJV, ASV; “city authorities”—NASV) is translated from the Greek word politarchas, and occurs only in Acts 17 verses 6 and 8. For many years, critics of the Bible’s claim of divine inspiration accused Luke of a historical inaccuracy because he used the title politarchas to refer to the city officials of Thessalonica, rather than employing the more common terms, strateegoi (magistrates) or exousiais (authorities). To support their accusations, they pointed out that the term politarch is found nowhere else in Greek literature as an official title. Thus, they reasoned that Luke made a mistake. How could someone refer to such an office if it did not exist? Whoever heard or read of politarchas in the Greek language? No one in modern times. That is, no one in modern times had heard of it until it was found recorded in the various cities of Macedonia—the province in which Thessalonica was located.

In 1960, Carl Schuler published a list of 32 inscriptions bearing the term politarchas. Approximately 19 out of the 32 came from Thessalonica, and at least three of them dated back to the first century (see McRay, 1991, p. 295). On the Via Egnatia (a main thoroughfare through ancient Thessalonica), there once stood a Roman Arch called the Vardar Gate. In 1867, the arch was torn down and used to repair the city walls (p. 295). An inscription on this arch, which is now housed in the British Museum, ranks as one of the most important when dealing with the term politarchas. This particular inscription, dated somewhere between 30 B.C. and A.D. 143, begins with the phrase, “In the time of Politarchas...” (Finegan, 1959, p. 352). Thus, the arch most likely was standing when Luke wrote his historical narrative known as Acts of the Apostles. And the fact that politarchs ruled Thessalonica during the travels of Paul, now stands as indisputable.

SERGIUS PAULUS THE PROCONSUL OF CYPRUS

Throughout the apostle Paul’s missionary journeys, he and his fellow travelers came in contact with numerous prestigious people—including Roman rulers of the area in which the missionaries were preaching. If Luke had been fabricating these travels, he could have made vague references to Roman rulers without giving specific names and titles. But that is not what one finds in the book of Acts. On the contrary, it seems that Luke went out of his way to document specific cities, places, names, and titles. Because of this copious documentation, we have ample instances in which to check his reliability as a historian.

One such instance is found in Acts 13. In that chapter, Luke documented Paul’s journey into Seleucia, then Cyprus, and Salamis, then Paphos. In Paphos, Paul and his companions encountered two individuals—a Jew named Bar-Jesus, and his companion Sergius Paulus, an intelligent man who summoned Paul and Barnabas in order to hear the Word of God (Acts 13:4-7). This particular reference to Sergius Paulus provides the student of archaeology with a two-fold test of Luke’s accuracy. First, was the area of Cyprus and Paphos ruled by a proconsul during the time of Paul’s work there? Second, was there ever a Sergius Paulus?

For many years, skeptics of Luke’s accuracy claimed that the area around Cyprus would not have been ruled by a proconsul. Since Cyprus was an imperial province, it would have been put under a “propraetor” not a proconsul (Unger, 1962, pp. 185-186). While it is true that Cyprus at one time had been an imperial province, it is not true that it was such during Paul’s travels there. In fact, “in 22 B.C. Augustus transferred it to the Roman Senate, and it was therefore placed under the administration of proconsuls” (Free and Vos, 1992, p. 269). Biblical scholar F.F. Bruce expanded on this information when he explained that Cyprus was made an imperial province in 27 B.C., but that Augustus gave it to the Senate five years later in exchange for Dalmatia. Once given to the Senate, proconsuls would have ruled Cyprus, just as in the other senatorial provinces (Bruce, 1990, p. 295). As Thomas Eaves remarked:

As we turn to the writers of history for that period, Dia Cassius (Roman History) and Strabo (The Geography of Strabo), we learn that there were two periods of Cyprus’ history: first, it was an imperial province governed by a propraetor, and later in 22 B.C., it was made a senatorial province governed by a proconsul. Therefore, the historians support Luke in his statement that Cyprus was ruled by a proconsul, for it was between 40-50 A.D. when Paul made his first missionary journey. If we accept secular history as being true we must also accept Biblical history, for they are in agreement (1980, p. 234).

In addition to the known fact that Cyprus became a senatorial province, archaeologists have found copper coins from the region that refer to other proconsuls who were not much removed from the time of Paul. One such coin, called appropriately a “copper proconsular coin of Cyprus,” pictures the head of Claudius Caesar, and contains the title of “Arminius Proclus, Proconsul…of the Cyprians” (McClintock and Strong, 1968, 2:627).

Even more impressive than the fact that Luke had the specific title recorded accurately, is the fact that evidence has come to light that the record of Sergius Paulus is equally accurate. It is interesting, in this regard, that there are several inscriptions that possibly could match the proconsul recorded by Luke. The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia (ISBE) records three ancient inscriptions that could be possible matches (see Hughes, 1986, 2:728). First, at Soli on the north coast of Cyprus, an inscription was uncovered that mentioned Paulus, who was a proconsul. The authors and editors of the ISBE contend that the earliest this inscription can be dated is A.D. 50, and that it therefore cannot fit the Paulus of Acts 13. Others, however, are convinced that this is the Paulus of Acts’ fame (Unger, 1962, pp. 185-186; see also McGarvey, n.d., 2:7). In addition to this find, another Latin inscription has been discovered that refers to a Lucius Sergius Paulus who was “one of the curators of the Banks of the Tiber during the reign of Claudius.” Eminent archaeologist Sir William Ramsay argued that this man later became the proconsul of Cyprus, and should be connected with Acts 13 (Hughes, 2:728). Finally, a fragmentary Greek inscription hailing from Kythraia in northern Cyprus has been discovered that refers to a Quintus Sergius Paulus as a proconsul during the reign of Claudius (Hughes, 2:728). Regardless of which of these inscriptions actually connects to Acts 13, the evidence provides a plausible match. At least two men named Paulus were proconsuls in Cyprus, and at least two men named Sergius Paulus were officials during Claudius’ reign. Luke’s accuracy is confirmed once again.

CONCERNING DEATH BY CRUCIFIXION

Throughout centuries of history, crucifixion has been one of the most painful and shameful ways to die. Because of the ignominy attached to this means of death, many rulers crucified those who rebelled against them. Historically, multiplied thousands have been killed by this form of corporal punishment. In a brief summary of several of the most notable examples of mass crucifixion, John McRay commented that Alexander Jannaeus crucified 800 Jews in Jerusalem, the Romans crucified 6,000 slaves during the revolt led by Spartacus, and Josephus saw “many” Jews crucified in Tekoe at the end of the first revolt (1991, p. 389). Yet, in spite of all the literary documentation concerning crucifixion, little, if any, physical archaeological evidence had been produced from the Bible Lands concerning the practice. As with many of the people, places, and events recorded in the Bible, the lack of this physical evidence was not due to a fabrication by the biblical author, but was due, instead, to a lack of archaeological information.

In 1968, Vassilios Tzaferis found the first indisputable remains of a crucifixion victim. The victim’s skeleton had been placed in an ossuary that “was typical of those used by Jews in the Holy Land between the end of the second century B.C. and the fall of Jerusalem in A.D. 70” (McRay, 1991, p. 204). From an analysis of the skeletal remains of the victim, osteologists and other medical professionals from the Hadassah Medical School in Jerusalem were able to determine that the victim was a male between the approximate ages of 24 and 28 who was about 5 feet 6 inches tall. Based on the inscription of the ossuary, his name seems to have been “Yehohanan, the son of Hagakol,” although the last word of the description is still disputed (p. 204). The most significant piece of the victim’s skeleton is his right heel bone. A large spike- like nail had been hammered through the right heel. Between the head of the nail and the heel bone, several fragments of olive wood were found lodged. Randall Price, in his book, The Stones Cry Out, suggested that the nail apparently hit a knot in the olive stake upon which this man was crucified, causing the nail and heel to be removed together, due to the difficulty of removing the nail by itself (1997, p. 309). [A full-color photograph of the feet portion of the skeleton (showing the nail) can be seen in an article, “Search for the Sacred” by Jerry Adler and Anne Underwood in the August 30, 2004 issue of Newsweek magazine (144[9]:38).]

|

| This rare find of a spiked nail through a human heelbone is the first archaeological evidence that the heels of crucified victims were nailed to a wooden cross, as described in the Bible. Credit: Zev Radovan, Jerusalem. |

As to the significance of this find, Price has provided an excellent summary. In years gone by, certain scholars believed that the story of Jesus’ crucifixion had several flaws, to say the least. First, it was believed that nails were not used to secure victims to the actual cross, but that ropes were used instead for this purpose. Finding a heel bone with a several-inch-long spike intact, along with the fragments of olive wood, is indicative of the fact that the feet of crucifixion victims were attached to the cross using nails. Second, it had been suggested that victims of crucifixion were not given a decent burial. Certain scholars even believed that the account of Jesus’ burial in the tomb of Joseph of Arimathea was contrived, since crucifixion victims like Jesus were thrown into common graves alongside other condemned prisoners. The burial of the crucified victim found by Tzaferis proves that, at least on certain occasions, crucifixion victims were given a proper Jewish burial (1997, pp. 308-311; cf. Adler and Underwood, 2004, 144[9]:39).

COUNTING QUIRINIUS

The precision with which Luke reported historical details has been documented over and over again throughout the centuries by archaeologists and biblical scholars. In every instance, wherever sufficient archaeological evidence has surfaced, Luke has been vindicated as an accurate and meticulously precise writer. Skeptics and critics have been unable to verify even one anachronism or discrepancy with which to try to discredit the biblical writers’ claims of being governed by an overriding divine influence.

However, observe the above-stated criterion that serves as the key to a fair and proper assessment of Luke’s accuracy: wherever sufficient archaeological evidence has surfaced. Skeptics often level charges against Luke and the other biblical writers on the basis of arguments from silence. They fail to distinguish between a genuine contradiction on the one hand, and insufficient evidence from which to draw a firm conclusion on the other. A charge of contradiction or inaccuracy within the Bible is illegitimate, and therefore unsustained, in those areas where evidence of historical corroboration is either absent or scant.

In light of these principles, consider the following words of Luke:

And it came to pass in those days that a decree went out from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be registered. This census first took place while Quirinius was governing Syria (Luke 2:1-2).

Some scholars have charged Luke with committing an error, on the basis of the fact that history records that Publius Sulpicius Quirinius was Governor of Syria beginning in A.D. 6—several years after the birth of Christ. It is true that thus far no historical record has surfaced to verify either the governorship or the census of Quirinius as represented by Luke at the time of Jesus’ birth prior to the death of Herod in 4 B.C. As distinguished biblical archaeologist G. Ernest Wright of Harvard Divinity School conceded: “This chronological problem has not been solved” (1960, p. 158).

This void in extant information (which would permit definitive archaeological confirmation) notwithstanding, sufficient evidence does exist to postulate a plausible explanation for Luke’s allusions, thereby rendering the charge of discrepancy ineffectual. Being the meticulous historian that he was, Luke demonstrated his awareness of a separate provincial census during Quirinius’ governorship beginning in A.D. 6 (Acts 5:37). In view of this familiarity, he surely would not have confused this census with one taken ten or more years earlier. Hence Luke observed that a priorcensus was, indeed, taken at the command of Caesar Augustus sometime prior to 4 B.C. He flagged this earlier census by using the expression prote egeneto (“first took place”)—which assumes a later one (cf. Nicoll, n. d., 1:471). To question the authenticity of this claim, simply because no explicit reference has yet been found, is unwarranted and prejudicial. No one questions the historicity of the second census taken by Quirinius around A.D. 6/7, despite the fact that the sole authority for it is a single inscription found in Venice. Sir William Ramsay, world-renowned and widely acclaimed authority on such matters, stated over one hundred years ago:

[W]hen we consider how purely accidental is the evidence for the second census, the want of evidence for the first seems to constitute no argument against the trustworthiness of Luke’s statement (1897, p. 386).

In addition, historical sources indicate that Quirinius was favored by Augustus, and was in active service of the emperor in the vicinity of Syria previous to, and during, the time period that Jesus was born. It is reasonable to conclude that Quirinius could have been appointed by Caesar to instigate a census/enrollment during that time frame, and that his competent execution of such could have earned for him a repeat appointment for the A.D. 6/7 census (see Archer, 1982, p. 366). Notice also that Luke did not use the term legatus—the normal title for a Roman governor. Rather, he used the participial form of hegemon that was used for a propraetor (senatorial governor), procurator (like Pontius Pilate), or quaestor (imperial commissioner) [see McGarvey and Pendleton, n.d., p. 28]. After providing a thorough summary of the historical and archaeological data pertaining to this question, Finegan concluded: “Thus the situation presupposed in Luke 2:3 seems entirely plausible” (1959, 2:261). Indeed it does.

GALLIO, PROCONSUL OF ACHAIA

Acts chapter 18 opens with a description of Paul’s ministry in the city of Corinth. It was there that he came into contact with Aquila and his faithful wife Priscilla, both of whom had been expelled from Rome at the command of Claudius, and who, as a result, had come to live in Corinth. Because they were tentmakers, like Paul, the apostle stayed with them and worked as a “vocational minister,” making tents and preaching the Gospel. As was usually the case with Paul’s preaching, many of the Jews were offended, and opposed his work. Because of this opposition, Paul told the Jews that from then on he would go to the Gentiles. That said, Paul went to the house of a man named Justus who lived next door to the synagogue. Soon after his proclamation to go to the Gentiles, Paul had a vision in which the Lord instructed him to speak boldly, because no one in the city would attack him. Encouraged by the vision, Paul continued in Corinth for a year and six months, teaching the Word of God among the people.

After Paul’s eighteen-month-long stay in Corinth, the opposition to his preaching finally erupted into violent, political action. Acts 18:12-17 explains.

When Gallio was proconsul of Achaia, the Jews with one accord rose up against Paul and brought him to the judgment seat, saying, “This fellow persuades men to worship God contrary to the law.” And when Paul was about to open his mouth, Gallio said to the Jews, “If it were a matter of wrongdoing or wicked crimes, O Jews, there would be reason why I should bear with you. But if it is a question of words and names and your own law, look to it yourselves; for I do not want to be a judge of such matters.” And he drove them from the judgment seat. Then all the Greeks took Sosthenes, the ruler of the synagogue, and beat him before the judgment seat. But Gallio took no notice of these things.

From this brief pericope of scripture, we learn several things about Gallio and his personality. Of paramount importance to our discussion is the fact that Luke recorded that Gallio was the “proconsul of Achaia.” Here again Luke, in recording specific information about the political rulers of his day, provided his readers with a checkable point of reference. Was Gallio ever really the proconsul of Achaia?

Marianne Bonz, the former managing editor of the Harvard Theological Review, shed some light on a now-famous inscription concerning Gallio. She recounted how, in 1905, a doctoral student in Paris was sifting through a collection of inscriptions that had been collected from the Greek city of Delphi. In these various inscriptions, he found four different fragments that, when put together, formed a large portion of a letter from the Emperor Claudius. The letter from the emperor was written to none other than Gallio, the proconsul of Achaia (Bonz, 1998, p. 8).

McRay, in giving the Greek portions of this now-famous inscription, and supplying missing letters in the gaps of the text to make it legible, translated it as follows:

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, Pontifex Maximus, of tribunician authority for the twelfth time, imperator twenty-sixth time.… Lucius Junius Gallio, my friend, and the proconsul of Achaia (1991, pp. 226- 227).

And while certain portions of the above inscription are not entirely clear, the name of Gallio and his office in Achaia are clearly legible. Not only did Luke accurately record the name of Gallio, but he likewise recorded his political office with equal precision.

The importance of the Gallio inscription goes even deeper than verification of Luke’s accuracy. This particular find shows how archaeology can give us a better understanding of the biblical text, especially in areas of chronology. Most scholars familiar with the travels and epistles of the apostle Paul will readily admit that attaching specific dates to his activities remains an exceedingly difficult task. The Gallio inscription, however, has added a piece to this chronological puzzle. Jack Finegan, in his detailed work on biblical chronology, dated the inscription to the year A.D. 52, Gallio’s proconsulship in early A.D. 51, and Paul’s arrival in Corinth in the winter of A.D. 49/50. Finegan stated concerning his conclusion: “This determination of the time when Paul arrived in Corinth thus provides an important anchor point for the entire chronology of Paul” (1998, pp. 391- 393).

A WORD ABOUT OSSUARIES

The Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land provides an excellent brief description of ossuaries in general. The writers explain that an ossuary is a box about 2.5 feet long, usually made out of clay or cut out of chalk or limestone, used primarily to bury human bones after the soft tissue and flesh have decomposed. Ossuaries, in fact,

are typical of the burial practices in Jerusalem and its vicinity during the Early Roman period, i.e., between c. 40 B.C. and A.D. 135. Ossuaries found in the Herodian cemetery in Jericho are dated by Hachlili to a more restricted time period of between A.D. 10-68 (“Ossuary,” 2001, p. 377).

Ossuary panels often had decorations on them, and many had inscriptions or painted markings and letters, indicating whose bones were inside.

Of interest is the fact that many of the ossuaries discovered to date contain the same names that we find in various biblical accounts. And, while we cannot be sure that the bones contained in the ossuaries are the bones of the exact personalities mentioned in the Bible, the matching nomenclature does show that the biblical writers at least employed names that coincided accurately with the names used in general during the time that the New Testament books were written.

Coming down the direct descent on the Mount of Olives is the site known as Dominus flevit, “the name embodying the tradition that this is the place where ‘the Lord wept’ over Jerusalem” (Finegan, 1992, p. 171). In 1953, excavations began in this area, and a large cemetery was discovered, consisting of at least five hundred known burial places. Among these many burial sites, over 120 ossuaries were discovered, more than 40 of which contained inscriptions and writing. Among the labeled ossuaries, the names of Martha and Miriam appear on a single ossuary. Other names that appear on the ossuaries are Joseph, Judas, Solome, Sapphira, Simeon, Yeshua (Jesus), Zechariah, Eleazar, Jairus, and John (Finegan, 1992, pp. 366-371). Free and Vos, in their brief critique of Rudolph Bultmann’s “form criticism,” used ossuary evidence to expose a few of the flaws in Bultmann’s ideas. They wrote:

[S]ome scholars formerly held that personal names used in the gospels, particularly in John, were fictitious and had been selected because of their meaning and not because they referred to historical persons. Such speculations are not supported by the ossuary inscriptions, which preserve many of the biblical names (1992, p. 256).

|

| The ornate nature of this ancient Jewish ossuary with the name “Caiphas” inscribed on it leads many biblical archaeologists to connect this burial box to the Caiaphas of the Bible. Credit: Zev Radovan, Jerusalem. |

Along these same lines, Price discussed several ossuaries that were found accidentally in 1990, when workers were building a water park in Jerusalem’s Peace Forest. Among the twelve limestone ossuaries discovered, one

was exquisitely ornate and decorated with incised rosette. Obviously it had belonged to a wealthy or high-ranking patron who could afford such a box. On this box was an inscription. It read in two places Qafa and Yehosef bar Qayafa (“Caiphas,” “Joseph, son of Caiphas”) [1997, p. 305].

Price connected this Caiphas to the one recorded in the Bible, using two lines of reasoning. First, the Caiaphas in the biblical record was an influential, prominent high priest who would have possessed the means to obtain such an ornate burial box. Second, while the New Testament text gives only the name Caiaphas, Josephus “gives his full name as ‘Joseph who was called Caiaphas of the high priesthood’ ” (1987, p. 305). Of further interest is the fact that the ossuary contained the bones of six different people, one of whom was a man around the age of 60. Are these the bones of the Caiaphas recorded in the New Testament? No one can be sure. It is the case, however, that many ossuary finds, at the very least, verify that the New Testament writers used names that were extant during the period in which they wrote.

A note of caution is needed regarding attempts to prove a direct connection between ossuary finds and biblical characters. The most famous such attempt thus far comes from the “James” ossuary that captured the world’s attention in late 2002. The inscription on that particular bone box reads: “James, the son of Joseph, brother of Jesus.” Was this the ossuary that contained the bones of Jesus Christ’s physical brother? In 2002, the answer remained to be seen. In a brief article I authored on this matter in December 2002, I wrote: “At present, we cannot be dogmatic about the ossuarial evidence” (Butt, 2002). Currently, the inscription still finds itself embroiled in debate. After analyzing the inscription, a committee appointed by the Israeli Antiquities Authority declared it to be unauthentic. According to Eric Myers, a Judaic-studies scholar at Duke University, “the overwhelming scholarly consensus is that it’s a fake” (as quoted in Adler and Underwood, 2004, 144[9]:38). However, Hershel Shanks, the distinguished editor of Biblical Archaeology Review, insists that the inscription remains antiquated and may possibly be linked to the Jesus and James of the Bible (Shanks, 2004; cf. Adler and Underwood, p. 38).

Whether or not the inscription is actually authentic remains to be seen. Yet, even if the inscription does prove to date to approximately the first century, that still would not prove that the ossuary contained the bones of Jesus’ physical brother. It would prove that names like Joseph, James, and Jesus were used during that time in that region of the world, which would, at the very least, verify that the biblical writers related information that fit with the events occurring at the time they produced their writings. As Andrew Overman, head of classics at Macalester College, stated: “Even if the [James] Ossuary is genuine, it provides no new information” (as quoted in Adler and Underwood, p. 39). When looking to archaeology, we must remember not to ask it to prove too much. The discipline does have limitations. Yet, in spite of those limitations, it remains a valuable tool that can be used to shed light on the biblical text. As Adler and Underwood remarked, the value of archaeology is “in providing a historical and intellectual context, and the occasional flash of illumination on crucial details” (p. 39).

GENTILES AND THE TEMPLE

Near the end of the book of Acts, the apostle Paul was making every effort to arrive in the city of Jerusalem in time to celebrate an upcoming Jewish feast. Upon reaching Jerusalem, he met with James and several of the Jewish leaders, and reported “those things which God had done among the Gentiles through his ministry” (Acts 21:19). Upon hearing Paul’s report, the Jewish leaders of the church advised Paul to take certain men into the temple in order to purify himself along with the men. While in the temple, certain Jews from Asia saw Paul, and stirred up the crowd against him, saying,

Men of Israel, help! This is the man who teaches all men everywhere against the people, the law, and this place; and furthermore he also brought Greeks into the temple and has defiled this holy place (Acts 21:28).

In the next verse, the text relates the fact that the men had seen Trophimus the Ephesian with Paul in the city, and they “supposed” that Paul had brought him into the temple (although the record does not indicate that anyone actually saw this happen).

In response to the accusation that Paul had defiled the temple by bringing in a Gentile, the text states that “all the city was disturbed; and the people ran together, seized Paul, and dragged him out of the temple; and immediately the doors were shut” (Acts 21:30). The next verse of Acts states explicitly what this violent mob planned to do with Paul: “Now as they were seeking to kill him, news came to the commander of the garrison that all Jerusalem was in an uproar.” Under what law or pretense was the Jewish mob working when it intended to kill Paul?

|

| The stone inscription forbidding Gentiles from entering the sanctified area of the temple in Jerusalem. Credit: Zev Radovan, Jerusalem. |

A plausible answer to this query comes to us from archaeology. In his description of the temple in Jerusalem, Josephus explained that a certain inscription separated the part of the temple that Gentiles could enter, from the portions of the temple that they could not enter. This inscription, says Josephus, “forbade any foreigner to go in, under pain of death” (Antiquities, 15:11:5). A find published in 1871 by C.S. Clermont- Ganneau brings the picture into clearer focus. About 50 meters from the actual temple site, a fragment of stone with seven lines of Greek capitals was discovered (see Thompson, 1962, p. 314). Finegan gives the entire Greek text, and translates the inscription as follows:

No foreigner is to enter within the balustrade and enclosure around the temple area. Whoever is caught will have himself to blame for his death which will follow (1992, p. 197).

In addition to this single inscription, another stone fragment was found and described in 1938. Discovered near the north gate of Jerusalem (also known as St. Stephen’s Gate), this additional stone fragment was er than the first, and had six lines instead of seven. The partially preserved words clearly coincided with those on the previous inscription. Finegan noted concerning the preserved words: “From them it would appear that the wording of the entire inscription was identical (except for aut instead of eautoo)….” As an interesting side note, Finegan mentioned that the letters of this second inscription had been painted red, and that the letters still retained much of their original coloration (1992, p. 197).

In light of these finds, and the comments by Josephus, one can see why the mob in Acts 21 so boldly sought to kill Paul. These inscriptions shed light on the biblical text, and in doing so, offer further confirmation of its accuracy.

CORBAN

On several occasions, Jesus was accosted by the Pharisees and other religious leaders, because He and His disciples were not doing exactly what the Pharisees thought they should be doing. Many times, the religious leaders had instituted laws or traditions that were not in God’s Word, but nonetheless were treated with equal or greater reverence than the laws given by God. In Mark 7:1-16, the Bible records that the Pharisees and other leaders were finding fault with the disciples of Jesus because Jesus’ followers did not wash their hands in the traditional manner before they ate. The Pharisees said to Jesus: “Why do your disciples not walk according to the tradition of the elders, but eat bread with unwashed hands?” (Mark 7:5).

Upon hearing this accusatory interrogation, Jesus launched into a powerful condemnation of the accusers. Jesus explained that His inquisitors often kept their beloved traditions, while ignoring the commandments of God. Jesus said: “All too well you reject the commandment of God, that you may keep your tradition” (Mark 7:9). As a case in point of their rejection of God’s Law, Christ went on to say:

For Moses said, “Honor your father and your mother”; and, “He who curses father or mother, let him be put to death.” But you say, “If a man says to his father or mother, ‘Whatever profit you might have received from me is Corban’ (that is, a gift to God),” then you no longer let him do anything for his father or his mother, making the word of God of no effect through your tradition which you have handed down. And many such things you do (Mark 7:11-13, emp. added).

In this passage, Jesus repudiated the Pharisees’ ungodly insistence upon their own traditions, and at the same time included a reference that can be (and has been) authenticated by archaeological discovery. Jesus mentioned the word corban, a word that the writer of the gospel account felt needed a little explanation. Mark defined the word as “a gift to God.” In a discussion of this term in an article by Kathleen and Leen Ritmeyer, the word comes into sharper focus. They documented a fragment of a stone vessel found near the southern wall of the temple. On the fragment, the Hebrew word krbn(korban—the same word used by Jesus in Mark 7) is inscribed (1992, p. 41). Of further interest is the fact that the inscription also included “two crudely drawn birds, identified as pigeons or doves.” The authors mentioned that the vessel might have been “used in connection with a sacrifice to celebrate the birth of a child” (Ritmeyer, 1992, p. 41). In Luke 2:24, we read about Joseph and Mary offering two pigeons when they took baby Jesus to present Him to God. Since these animals were the prescribed sacrifice for certain temple sacrifices, those who sold them set up shop in the temple. Due to the immoral practices of many such merchants, they fell under Jesus’ attack when He cleansed the temple and “overturned the tables of the moneychangers and seats of those who sold doves” (Mark 11:15).

CONCLUSION

Over and over, biblical references that can be checked, prove to be historically accurate in every detail. After hundreds of years of critical scrutiny, both the Old and New Testaments of the Bible have proven their authenticity and accuracy at every turn. Sir William Ramsay, in his assessment of Luke’s writings in the New Testament, wrote:

You may press the words of Luke in a degree beyond any other historian’s, and they stand the keenest scrutiny and the hardest treatment, provided always that the critic knows the subject and does not go beyond the limits of science and of justice (1915, p. 89).

Today, almost a hundred years after that statement originally was written, the exact same thing can be said with even more certainty of the writings of Luke—and every other Bible writer. Almost 3,000 years ago, the sweet singer of Israel, in his description of God’s Word, put it perfectly when he said: “The entirety of Your word is truth” (Psalm 119:160).

REFERENCES

Adler, Jerry and Anne Underwood (2004), “Search for the Sacred,” Newsweek, 144[9]:37-41, August 30.

Archer, Gleason L. Jr. (1982), Encyclopedia of Bible Difficulties (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan).

Blaiklock, E.M. (1984), The Archaeology of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan), revised edition.

Bonz, Marianne (1998), “Recovering the Material World of the Early Christians,” [On-line], URL: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/maps/arch/re covering.html.

Bruce, F.F. (1990), The Book of Acts (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans), third revised edition.

Butt, Kyle (2002), “James, Son of Joseph, Brother of Jesus,” [On-line], URL: http://www.apologeticspress.org/articles/495.

Eaves, Thomas F. (1980), “The Inspired Word,” Great Doctrines of the Bible, ed. M.H. Tucker (Knoxville, TN: East Tennessee School of Preaching).

Finegan, Jack (1959), Light from the Ancient Past (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), second edition.

Finegan, Jack (1992), The Archeology of the New Testament (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), revised edition.

Finegan, Jack (1998), Handbook of Biblical Chronology (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson).

Free, Joseph P. and Howard F. Vos (1992), Archaeology and Bible History (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan).

Hughes, J.J. (1986), “Paulus, Sergius,” International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, ed. Geoffrey W. Bromiley (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans), revised edition.

Josephus, Flavius (1987 edition), Antiquities of the Jews, in The Life and Works of Flavius Josephus, transl. William Whiston (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson).

McClintock, John and James Strong (1968 reprint), “Cyprus,” Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker).

McGarvey, J.W. (no date), New Commentary on Acts of Apostles (Delight, AR: Gospel Light).

McGarvey, J.W. and Philip Y. Pendleton (no date), The Fourfold Gospel (Cincinnati, OH: The Standard Publishing Foundation).

McRay, John (1991), Archaeology and the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker).

Nicoll, W. Robertson (no date), The Expositor’s Greek Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans).

“Ossuary” (2001), Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land, ed. Avraham Negev and Shimon Gibson (New York: Continuum).

Price, Randall (1997), The Stones Cry Out (Eugene, OR: Harvest House).

Ramsay, William M. (1897), St. Paul the Traveller and the Roman Citizen (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1962 reprint).

Ramsay, William M. (1915), The Bearing of Recent Discovery on the Trustworthiness of the NewTestament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1975 reprint).

Ritmeyer, Kathleen and Leen Ritmeyer (1992), “Reconstructing Herod’s Temple Mount in Jerusalem,” Archaeology and the Bible: Archaeology in the World of Herod, Jesus and Paul, ed. Hershel Shanks and Dan P. Cole (Washington, D.C.: Biblical Archaeology Review).

Shanks, Hershel (2004), “The Seventh Sample,” [On-line], URL: http://www.bib-arch.org/bswbbreakingseventh.html.

Thompson, J.A. (1962), The Bible and Archaeology (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans).

Thompson, J.A. (1987), The Bible and Archaeology (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans), third edition.

Unger, Merrill (1962), Archaeology and the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan).

Wright, G. Ernest (1960), Biblical Archaeology (Philadelphia, PA: Westminster).

No comments:

Post a Comment